February Newsletter 2026

SPECIAL VALENTINE’S OFFER

from February 14th to 21st

‘ROUNDHEADS & CAVALIERS’

books 1 and 2 are both 0.99c/0.99p

And for February’s trivia …

“Strange (or mythical?) Scottish creatures”

Reports of big cats from various parts of Britain go back to medieval times and have become an established part of Scottish folklore.

The Beast of Buchan is perhaps the best known of them.

In the tales, The Beast is a large black cat similar to a panther which preys on local livestock.

Instances of sheep being attacked by The Beast became so prolific that it has been raised on more than one occasion in the Scottish Parliament.

All who see it are certain that it is not a native Scottish wildcat.

On the other hand, it could be a lynx or a puma or a black panther.

It's the size of a Labrador or an Alsatian or a greyhound but it’s definitely not a dog or a fox.

There have been so many sightings that the Beast now has its own set of stalkers called the Scottish Big Cat Trust.

This dedicated group investigates sightings whenever and wherever they occur.

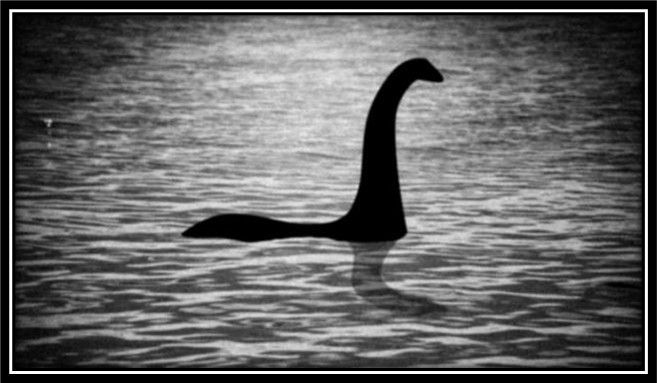

Most famous of all is the Loch Ness Monster.

Sightings of Nessie before the 20th century were very few.

But two sightings in the summer of 1933 changed everything and created a media sensation.

Nessie fits a tradition of ‘lake monsters’ which are supposed to exist elsewhere in Scotland as well as in other parts of the world – such as Storsjöodjuret in Sweden.

In the 1980s, the Swedish authorities sought British advice on legal protection for their monster (should it exist) from poachers and adventurers.

After much consultation, it was concluded that Nessie was already protected under the 1981 Wildlife & Countryside Act.

As such it would be a criminal offence to

“snare, shoot or blow Nessie up with explosives".

Following this advice, Sweden went on to pass legislation offering similar protection to the Storsjőodjuret.

For centuries, the haggis remained one of Scotland’s most closely-guarded secrets.

These small animals – long supposed to be mere folklore – have begun to capture the attention of wildlife enthusiasts everywhere as recent discoveries reveal a rich ecosystem of haggis species.

The Haggis Scoticus is a small, furry mammal.

Averaging 30-40 cm in length, these rotund creatures are perfectly adapted to life in the rugged Scottish landscape.

Their most distinctive features are their asymmetrical legs – shorter on one side than the other; this is an evolutionary marvel that allows them to navigate steep hillsides swiftly.

The right-running haggis (known as the Rightie) is characterised by its unique leg adaptation allowing it to run uphill clockwise.

The left-running haggis (or Leftie) has shorter legs on its left side, enabling it to run counterclockwise.

Some believe haggis lore dictates that ‘lefties’ do not mate with ‘righties’ but this is debatable.

The term for a group of wild haggis is "stooshie." This collective noun is commonly used to refer to these small mammals found in Scotland's rugged terrain.

Haggis populations are spread right across Scotland but the highest concentrations are found in the Highlands and the Scottish borders.

Haggi (this is not a typo; it is the correct plural of haggis) prefer areas with a mixture of heather moorland and scattered woodlands – places which provide convenient shelter.

Three common haggis species have been identified, each adapted to its specific habitat.

The Highland Haggis (Haggis Montanus) is larger and woollier than its lowland cousins.

A remarkable species indigenous to the Highlands.

It is distinguished by its impressive adaptations to thrive in the challenging environment of these elevated terrains.

The Loch Haggis (Haggis Aquaticus) is a rare loch-dwelling species of wild haggis known for its webbed toes, a water-proof coat and tartan nests with the uncanny ability to vanish into the mist.

Long thought extinct (or imaginary), sightings of this elusive creature continue to surface near remote Scottish lochs.

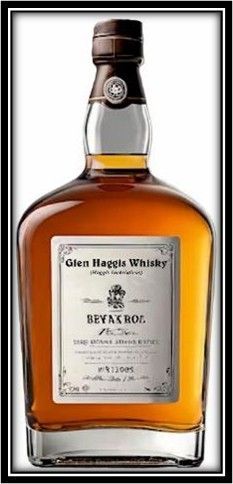

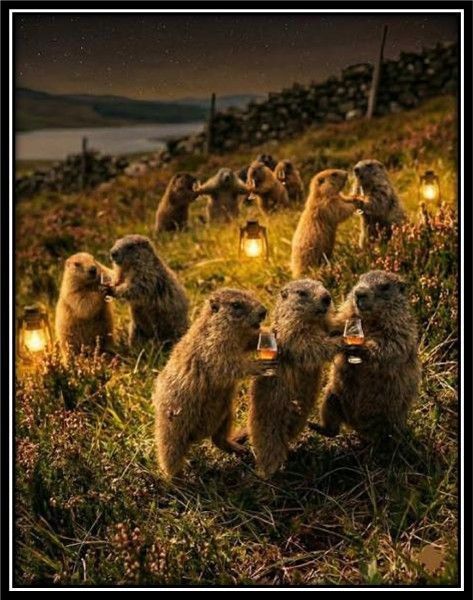

The Whisky Glen Haggis (Haggis Inebriaticus) can usually be found near distilleries, is mostly nocturnal and has a tendency to lurch or wobble when walking.

The preferred diet of all 3 species is interesting – even unique. They eat ‘Tunnocks’ tea cakes and drink single malt whisky (when they can get it) and ‘Irn Bru’ (when they can’t).

For those unfamiliar with the Tunnock tea cake it is a biscuit base topped with a marshmallow dome and covered in chocolate. They are easy to spot, being wrapped in red and silver foil.

This period, known as the Great Haggis Gathering, is when elaborate courtship displays take place and one may sometimes hear the males’ distinctive mating call – which sounds something like a cross between a whistle and a bagpipes’ drone.

Haggis are generally solitary creatures but they come together during the mating season in late autumn.

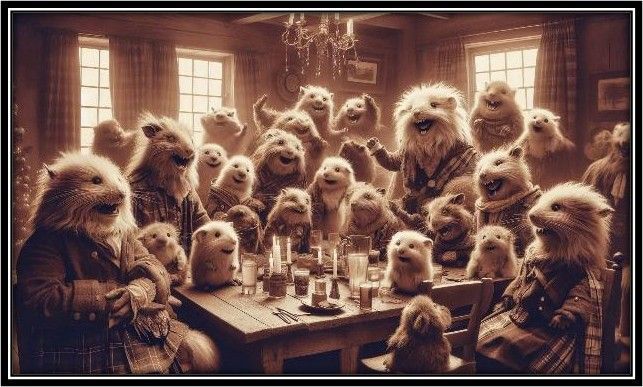

The image above might be of Hogmanay but is more likely to be the main highlight of the Haggis calendar; the January 26th Celebration – marking the annual triumph of once again outwitting the Burns Night Hunters.

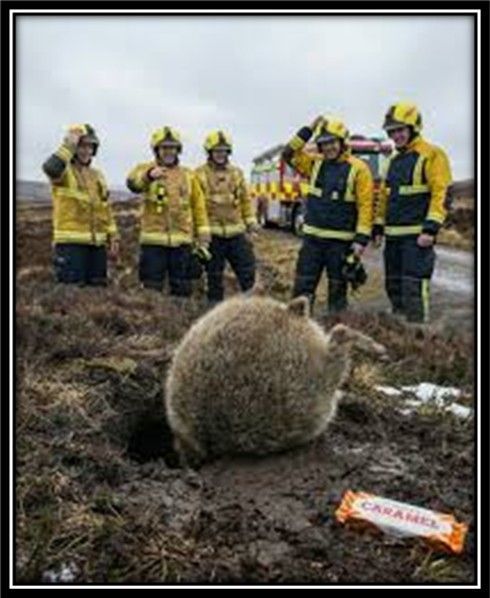

While to the left we see a typical Burns Night Celebration in many pubs throughout Scotland!

Cheers or as the Scots say ...

Slàinte Mhath!

While not currently endangered, the Scottish Wildlife Trust has put in place several conservation programmes including: -

‘Haggis Highways’ to allow safe passage between fragmented habitats.

And ‘Haggis Tunnels’ beneath the busiest roads.

Unfortunately, a haggis (often the Haggis Inebriaticus) sometimes mistakes a rabbit-hole for a tunnel – with the obvious unfortunate result and thus creating a job for the emergency services.

Welcome to February Newsletter 2026